What you should know about constraints in PostgreSQL

In this blog, we explore Postgres constraints through the pg_constraint catalog, covering table vs. column constraints, constraint triggers, domains and more.

Author

Gulcin Yildirim JelinekDate published

At PGConf.EU this year, I presented my new talk "What you should know about constraints in PostgreSQL (and what's new in 18)". In this blog post, I will go deeper into some of the topics I've covered there. If you'd like to jump straight to the slides, here is the link.

On stage at PGConf.EU in Riga

What is a constraint?

When you define a table (or a column), you can attach rules that check or enforce something about the data. These rules are called constraints.

Data types also restrict the kind of data a column can hold but they’re often too general. For example, you can’t make a numeric type accept only positive values. To handle more specific rules (like ensuring unique product numbers or positive prices), SQL lets you define constraints on columns and tables.

Constraints give you fine-grained control over data integrity and if any inserted or default value violates them, PostgreSQL raises an error.

In short, constraints are rules enforced by the database to keep your data valid and consistent. When constraints are not enforced, data issues start to leak in and eventually turn into bugs. Spending time understanding constraints helps prevent subtle data bugs later on.

pg_constraint catalog

There is another way to look at constraints. Internally, constraints are all represented as rows in the pg_constraint catalog.

🗄️ What is a catalog?

In Postgres, a catalog is simply a system table, a table that PostgreSQL itself uses to keep track of the database’s internal metadata. Your tables store your data (e.g., users, orders, products), Postgres catalogs store Postgres’s data about your data (e.g., which tables exist, which columns they have, what constraints, what indexes etc.) So in that sense, the catalogs are Postgres’s internal database about the database.

There are many catalogs like pg_constraint:

pg_class: Every table, index, sequence, view, materialized view, TOAST table, composite type, foreign table, partitioned table and partitioned indexpg_attribute: The columns of those tables (column names, types, whether it is an identity or generated column, the column’s compression method, etc.)pg_type: Data types (built-ins, domains, user-defined types)pg_namespace: Schemaspg_index: Some information about indexes (the rest is mostly inpg_class)pg_proc: Functions, procedures, aggregate functions, window functions

Each one is a real table that lives inside the pg_catalog schema. Every database contains a pg_catalog schema, in addition to public and user-created schemas. You don’t need to prefix catalog tables with pg_catalog, because the pg_catalog schema is (implicitly searched) first in PostgreSQL’s search_path.

The catalog pg_constraint stores check, not-null, primary key, unique, foreign key, and exclusion constraints on tables.As the documentation for pg_constraint states, all constraints are listed in this catalog. If you checked the same page in versions prior to Postgres 18, you would notice a warning explaining that not-null constraints on relations are not represented here but instead in pg_attribute, as they only started getting their own entries in this catalog with Postgres 18! We'll talk more about this later.

Postgres 17:

The catalogpg_constraintstores check, primary key, unique, foreign key, and exclusion constraints on tables, as well as not-null constraints on domains.

Not-null constraints on relations are represented in thepg_attributecatalog, not here.

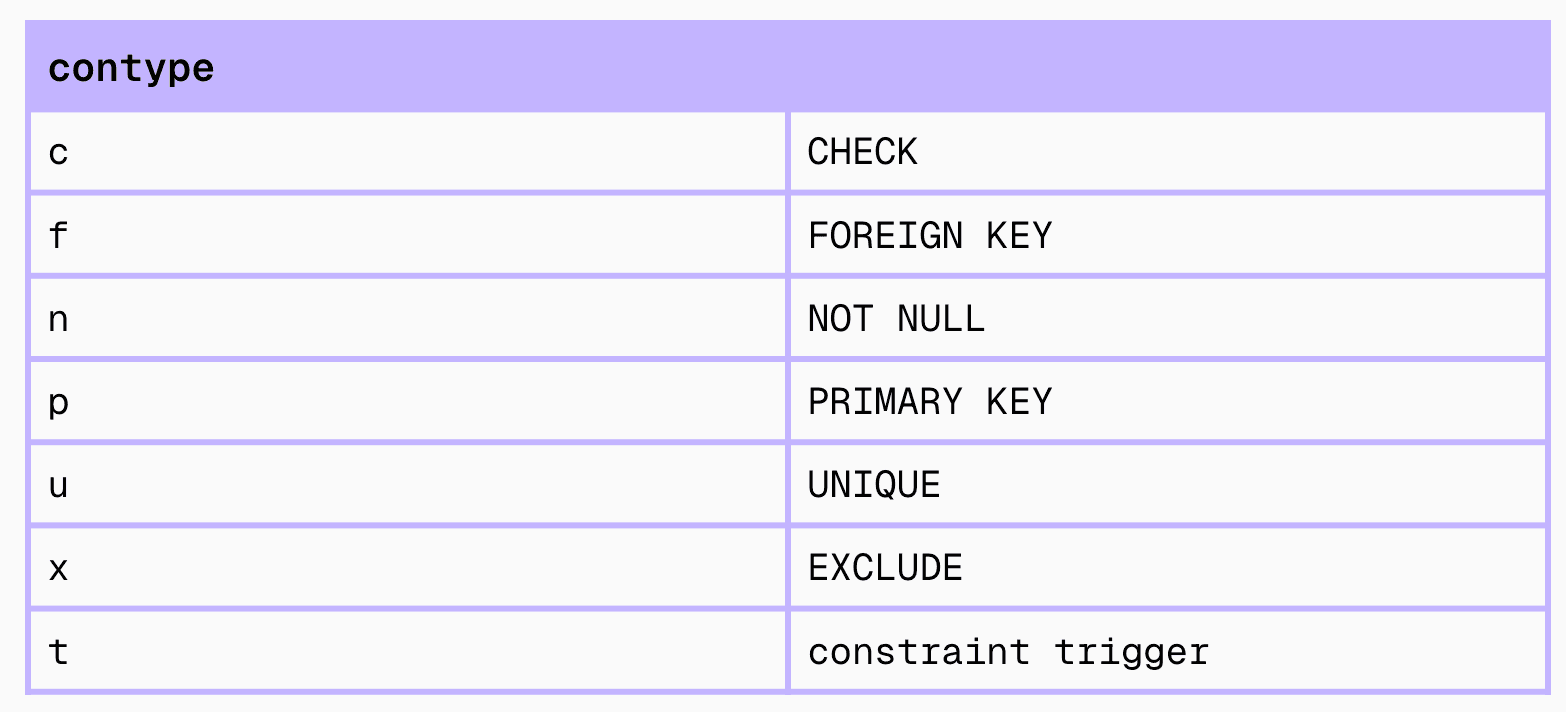

So, each constraint is recorded in this table with a corresponding contype . We will also talk more about them later on, especially the unusual one represented with a t 🙂

Column constraints vs table constraints

Let's keep reading pg_constraint documentation:

Column constraints are not treated specially. Every column constraint is equivalent to some table constraint.

In PostgreSQL’s internal catalog, there is no real distinction between column constraints and table constraints. For the SQL user, there are two syntaxes as seen below:

A column constraint is written right after a column’s definition (the first query). It applies to that one column only.

A table constraint is written after all the columns are listed (the second query). It can apply to one or more columns.

To Postgres internally, there's one representation, always a row in pg_constraint. That's why we can do ALTER TABLE.. DROP CONSTRAINT.. regardless of how it was written. There is no column constraint flag inside the catalog. A column constraint is just a table constraint that happens to involve one column.

Let's write a query to check the constraints on our two example tables (products_oct and products_nov) to see whether there are any differences between the constraints we just created:

⚡ Insights about the query

pg_classstores metadata about all relations.relnameis the plain table name, we get it by joiningpg_class rel ON rel.oid = c.conrelidbecausepg_constraintonly stores a reference (OID) to the table, not the name itself.conrelidis the OID of the table constraint belongs to. The join connects each constraint to its owning table.c.connameis the name of the constraint. Constraint names are unique per table, not globally. Names can be auto-generated by Postgres or can be explicitly defined in DDL.c.contyperepresents the type of the constraint (c,f,n,p,u,x,t).c.conkeyan array of attribute numbers representing the columns involved in the constraint (for example{1}→ the first column in the table,{1,3}→ columns 1 and 3).pg_get_constraintdef()is a system function for obtaining the definition of a constraint.

The (expanded) output of the query looks like this. As you can see, there is pretty much no difference between the column constraint and the table constraint aside from the tables they're attached to and the names Postgres generated for them.

Constraint trigger

Again, let's keep reading pg_constraint documentation:

User-defined constraint triggers (created with CREATE CONSTRAINT TRIGGER) also give rise to an entry in this table.Remember the contype table from earlier, where standard constraints like UNIQUE is represented with u, CHECK constraints with c, etc. Then there is also a t for constraint trigger?!

I don't think this is very well known. We're familiar with triggers and constraints in Postgres, but there's also something called a constraint trigger. What is that exactly?

Deferrable triggers

Constraint triggers are created using the CREATE CONSTRAINT TRIGGER command. It's almost like creating a regular trigger (CREATE TRIGGER) but when you specify the CONSTRAINT option, you end up with a constraint trigger instead. The main difference - and the biggest benefit in my opinion - is that we can now adjust the timing of the trigger firing using SET CONSTRAINTS.

SET CONSTRAINTSsets the behavior of constraint checking within the current transaction.IMMEDIATEconstraints are checked at the end of each statement.DEFERREDconstraints are not checked until transaction commit.

Normal triggers fire immediately after or before the event and you can't defer them. Constraint triggers, on the other hand, integrate with the constraint system and can be declared DEFERRABLE or INITIALLY DEFERRED just like constraints. This means you can delay their execution until COMMIT and control them at runtime with SET CONSTRAINTS.

⚠️ WHEN conditions are evaluated immediately

One minor detail to know about deferrability is that even if a constraint trigger itself is deferred, its WHEN clause is not. Postgres decides whether to queue the trigger immediately based on that WHEN condition. So if your WHEN clause filters out rows, that decision happens right away.

AFTER triggers

When creating a trigger, you have to specify whether the function is called BEFORE, AFTER or INSTEAD OF the event. A constraint trigger can only be specified as AFTER.

Constraint triggers are not meant to change the data flow, only to check conditions after the fact. The idea behind constraints is data validation while triggers are usually about data modification. Constraint triggers belong to the validation category and are expected to raise an exception when the constraints they implement are violated.

FOR EACH ROW triggers

When creating a trigger, you can specify whether the trigger function should be fired once every row affected by the trigger event using FOR EACH ROW or just once per SQL statement using FOR EACH STATEMENT.

Constraint triggers can only be specified as FOR EACH ROW. That's because constraint enforcement depends on the individual row values.

I keep saying "when creating a trigger" as opposed to "creating or replacing a trigger" because OR REPLACE option is not supported for constraint triggers.

Why constraint triggers exist

In his blog post "Triggers to enforce constraints in PostgreSQL", Laurenz Albe says:

Sometimes you want to enforce a condition on a table that cannot be implemented by a constraint. In such a case it is tempting to use triggers instead.

He also gives a good example of how this could be used and shows how MVCC behavior differs between constraints and triggers. I'd recommend giving it a read.

In practice though, most users will never create a constraint trigger by hand. Postgres primarily uses them internally as a building block for constraint enforcement. Foreign keys in particular are implemented using automatically generated constraint triggers. This design is what makes DEFERRABLE and INITIALLY DEFERRED foreign keys possible.

Domain

One last look at the pg_constraint documentation:

Check constraints on domains are stored here, too.

So, now we see a mention of domains 😊 I think this is another not-very-well-known concept.

🧱 What is a domain?

A domain is like a custom data type with rules attached. It is built on top of an existing base type (text, integer etc.) but you can add default values, NOT NULL or CHECK constraints. It is a way to centralize data rules instead of repeating them across multiple tables.

Let's have a quick example to see how domains work:

The example defines a new type called email_address. Now every column of that type automatically checks the regex when inserting or updating values. If you try to insert anything other than a valid email, it fails even though the table itself has no explicit CHECK constraint.

Generally, constraints belong to tables, but Postgres also lets you attach constraints on domains also as mentioned in the pg_constraint documentation above. I wanted to show how we can query those constraints that are attached to domains in the query below:

⚡ Insights about the query

pg_constraintstores all kind of constraints including domain constraints. The difference between them is which object type they're attached to.pg_typestores information about data types including domains.c.contypidis the OID of the domain type the constraint belongs to. The key details here is, whencontypidis non-zero, the constraint is attached to a domain instead of a table. Ifcontypidis zero, then the constraint is attached to a table, where we'd look atconrelidinstead.JOIN pg_type t ON t.oid = c.contypidthis join links each constraint to the domain that owns it. We can get the domain name (t.typname).c.contype = 'c'since domains only supportCHECKconstraints, we filter for'c'.pg_get_constraintdef()is a system function for obtaining the definition of a constraint (similar to what you'd see in aCREATE DOMAINstatement)

So, the key difference between table constraints and constraints on domains is that table constraints use conrelid to point to a table while domain constraints use contypid to point to a type (the domain).

And the output of our query looks like this, listing the constraint name, definition and domain name:

Conclusion

In this blog, we covered what constraints mean in Postgres by walking through the pg_constraint catalog documentation and demonstrating concepts such as table constraints vs. column constraints, constraint triggers and domains using simple SQL queries.

Next, we will continue with the newly introduced temporal keys in Postgres 18.

Bonus: If you'd like to try Postgres 18 on Xata, you can get access today.

Related Posts

Going down the rabbit hole of Postgres 18 features

A comprehensive list of PostgreSQL 18 new features, performance optimizations, operational and observability improvements, and new tools for devs.

Anatomy of Table-Level Locks in PostgreSQL

This blog explains locking mechanisms in PostgreSQL, focusing on table-level locks that are required by Data Definition Language (DDL) operations.

Anatomy of table-level locks: Reducing locking impact

Not all operations require the same level of locking, and PostgreSQL offers tools and techniques to minimize locking impact.

PGConf.EU Community Events Day: CfPs closing soon

PGConf.EU’s first Community Events Day organized by community members: summits, showcases and trainings. Last few days to submit talks!

Recap of PGConf.EU 2024 in Athens

My notes from PGConf.EU 2024 in Athens, Greece. Talks, extension summit, diversity committee meeting, Xata Postgres dinner, and more!

What I look forward to at PGConf.EU in Athens

The 14th PostgreSQL Conference in Europe is taking place in Athens, Greece from 22-25 October 2024. In this blog post, I will be sharing what I look forward to at PGConf.EU 2024 including a great keynote, extension ecosystem summit, Xata dinner and more.