Anatomy of Table-Level Locks in PostgreSQL

This blog explains locking mechanisms in PostgreSQL, focusing on table-level locks that are required by Data Definition Language (DDL) operations.

Author

Gulcin Yildirim JelinekDate published

Art of locking or unlocking?

It is common to think about database locks by drawing analogies to physical locks, which might even lead you to order books on the history of locks, Persian locks, and lock-picking techniques. Probably most of us learn by going deeper into the term "locking" to understand a concept in PostgreSQL that doesn’t have much to do with physical locks at all, which are primarily about security. Postgres locks though are all about concurrency and controlling which transaction can hold a lock while another transaction can do its thing, ideally without ever blocking each other. But as we know, no world is ideal, whether it’s a door lock or an AccessShareLock.

However, now that I’ve bought those said books about locks, I think I should be allowed to draw some parallels between, let’s say, the art of lock-picking and database locking mechanisms. There is one thing I will start with: to be able to pick a lock, any type of lock, you need to have a deep understanding of its inner workings; how the pins, tumbler, and mechanisms interact. By manipulating them, you can find the correct position to unlock the door or safe without a key! In the same way, to be able to manage database locks, you need to understand the internal workings of a database, and mainly how concurrency works in Postgres.

A short primer on MVCC

PostgreSQL uses Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC) to avoid many of the locking issues traditionally associated with databases. MVCC works by:

- Writing new copies of data rather than modifying rows in place.

- Ensuring that reads don’t block writes, and writes don’t block reads.

When a transaction updates data, Postgres creates a new version of the row while keeping the old version. Each row version contains system columns that are invisible to users but crucial for MVCC:

xmin: Transaction ID that created this versionxmax: The transaction ID that deleted/updated this version (null if current)cmin,cmax: Command IDs within the transactionctid: Physical location of the row version

With the default Read Committed Isolation Level, every time a statement begins, Postgres creates a snapshot containing:

- All active transaction IDs at that moment

- The latest committed transaction ID

- The list of in-progress transactions

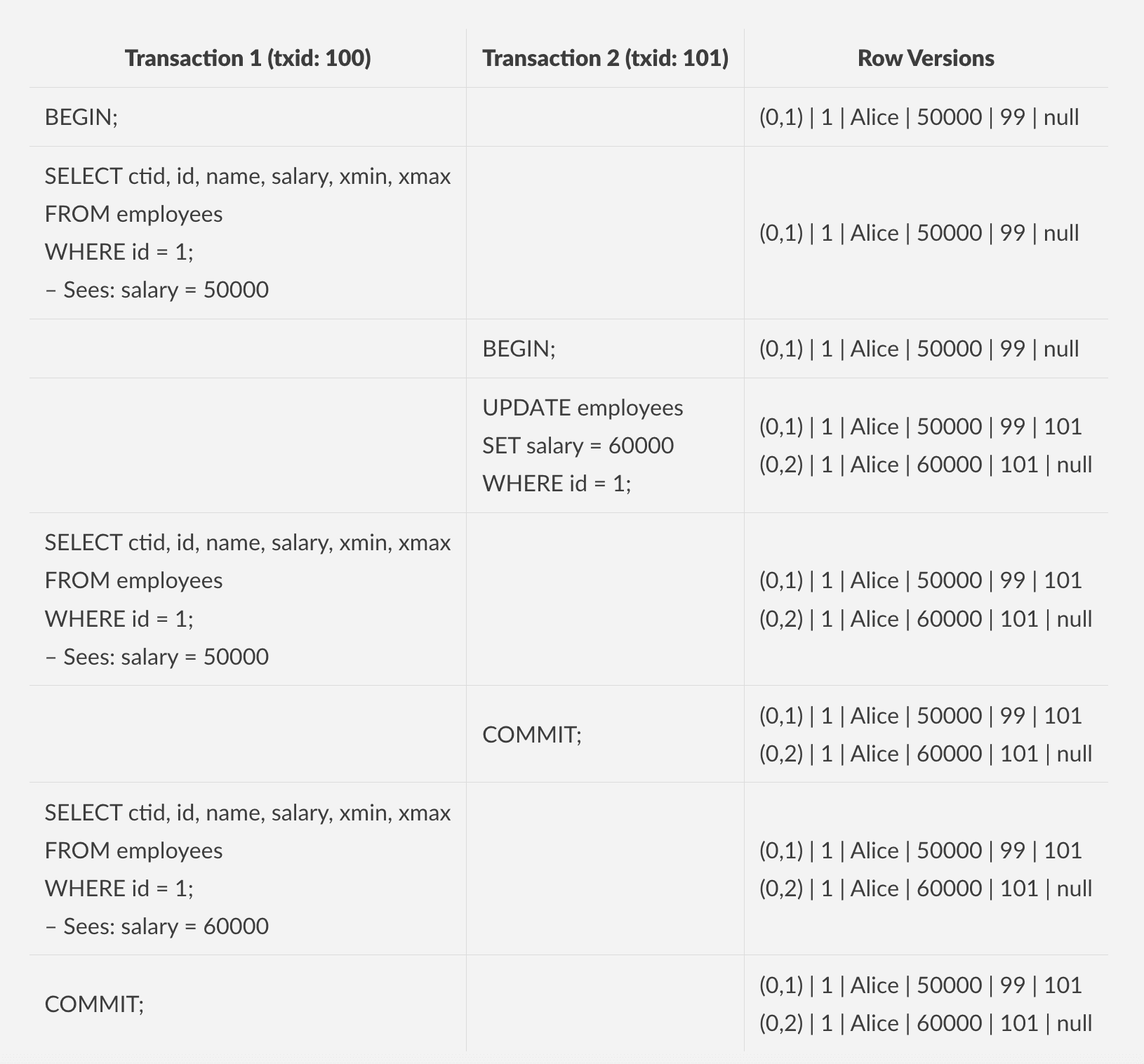

Let's see how it works in practice with Read Committed isolation level:

MVCC example

So to summarize, a single row exists with Alice's salary at 50000. First transaction (txid:100) starts and gets a snapshot for its SELECT statement and sees Alice's salary at 50000 because the row's xmax is null (meaning it's current), the row's xmin (99) is less than our transaction ID (100) and transaction 99 is already committed.

The second transaction (txid:101) updates the salary to 60000. This creates two row versions; old version marked with xmax=101, new version created with xmin=101. Then second transaction commits, making its changes visible to any new snapshots.

When the first transaction executes its second SELECT statement (before Transaction 2 commits), it still sees salary 50000 because Transaction 101 hasn't committed yet. After Transaction 2 commits, when Transaction 1 executes its third SELECT statement, it gets a fresh snapshot (Read Committed behavior) and now sees salary 60000 because:

- Each statement gets a new snapshot

- Transaction

101is now committed - The row version with

xmin=101is the current version (xmaxis null) - The old version with

xmax=101is no longer visible to new snapshots

This behavior is specific to Read Committed isolation level, where each statement gets a fresh snapshot and can see committed changes from other transactions, even within the same transaction.

But, of course, MVCC approach also comes with some implications:

- Dead row versions accumulate until cleaned by

VACUUM - Database size may temporarily grow due to keeping multiple versions

- Regular

VACUUMmaintenance is essential for performance

To finish up with clear benefits, MVCC design allows Postgres to provide consistent snapshots for long-running queries (hopefully they won't run too long 😄), high concurrency for mixed read-write workloads and strong isolation without excessive locking. While MVCC design is not specific to PostgreSQL, thanks to this approach we have most of concurrency issues sorted.

The purpose of locking

All locking, whatever their type is, will reduce the throughput, and potentially increase the latency, which means a loss of performance, as nothing is ever free. If my intention is to make sure my data does not have corruption and everyone is getting a correct result at their time of query, I have to agree that I'd have to lock access when multiple transactions are targeting the same table or same row to make sure we take some time to keep the order of things instead of showing wrong results, fast.

But we cannot also keep a lock too long, as that also comes with consequences. Let's imagine the two extremes: we never lock any transaction. A long-running financial report is calculating averages across departments while HR is processing year-end raises, and simultaneously, we try to add a new audit column. In PostgreSQL, even without explicit locks, adding a column requires an AccessExclusiveLock on the table. If we somehow bypassed this (imagine a hypothetical unsafe mode), we would be looking at a real chaos: the salary updates might fail as they encounter different table structures mid-transaction, and subsequent queries could face data corruption as the system catalog becomes inconsistent with actual table data. As hectic as it sounds, not locking anything would create different degrees of mess.

Now, let's consider the other extreme: we are locking every operation and each of them waits for another; one finishes, and the other one starts. We block the whole table for one query that is reading. That would also be okay if a few users, maybe using a small database, never had to query the same table ever at the same time; like a single-user accounting system running nightly reports.

The moment we have to serve multiple users at the same time, we will have to accept a level of isolation, so we make sure we agree to a standard that ensures we don't get dirty reads or phantom reads and such. This is why Postgres offers different isolation levels from Read Committed to Serializable.

DDL locks

MVCC approach makes PostgreSQL highly efficient for concurrent DML operations. Instead of modifying data in place, writes create new copies of the data, allowing reads and writes to proceed without blocking each other. However, even in an MVCC-based system, some level of locking is unavoidable. Reads may not block writes, but they still acquire lightweight locks on database objects like tables, types, and views.

So, MVCC protects you from writes blocking reads, but not from object locks taken by DDL commands. Different variants of the same DDL command may require varying levels of lock strength.

For DDL operations (e.g., ALTER TABLE or VACUUM FULL), stronger locks are often required, potentially blocking other operations. Such operations may block other DDL commands, DML operations, or even SELECT queries that are trying to access the same object. The complexity increases as each DDL command (and sometimes even sub-commands) has its own specific locking requirements, making it crucial to understand the implications of schema modifications in a busy database.

Table-level lock modes

Let's look at the various table-level lock modes, each serving different operations:

- ACCESS SHARE: The most basic lock used by

SELECToperations, multiple transactions can hold this lock simultaneously, least restrictive. - ROW SHARE: Used by

SELECT FOR UPDATE/SHARE, compatible with most other locks except exclusive locks. - ROW EXCLUSIVE: Required for DML operations (

INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE/MERGE) - SHARE UPDATE EXCLUSIVE: Used by maintenance operations like

VACUUM,ANALYZE, andCREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY, conflicts withShareLock,ShareRowExclusiveLock,ExclusiveLock,AccessExclusiveLock. - SHARE: Needed for

CREATE INDEX - SHARE ROW EXCLUSIVE: Used when creating triggers

- EXCLUSIVE: Required for operations like

REFRESH MATERIALIZED VIEW CONCURRENTLY - ACCESS EXCLUSIVE: The strongest lock, used by operations like

DROP TABLE,TRUNCATE, certainALTER TABLEcommands, andVACUUM FULL. Most restrictive, blocks all concurrent access and required for most schema modifications.

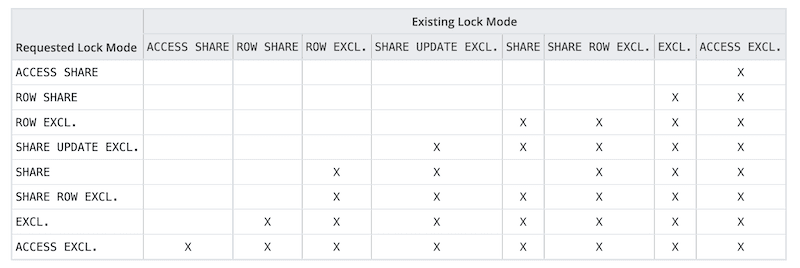

I think, knowing which operations gets what lock is important, but can be easily checked. Probably understanding how lock modes interact with each other is more crucial. Different lock modes conflict with different other modes.

Conflicting lock modes

There are a few key points to understand, ACCESS EXCLUSIVE conflicts with everything, including ACCESS SHARE (SELECT). Postgres has many optimizations to take weaker lock modes when it can. However, nothing is perfect, it will still take strong locks on some DDL operations. Once a transaction takes a strong lock, it holds it even if the statement has finished.

A critical lesson is that DDL operations may block both writes and reads for the entire duration of the transaction. Because of this, it's crucial to avoid mixing commands that require strong locks with others in the same transaction. For example, if you need to perform both a table alteration and data updates, it's better to separate these into different transactions to minimize blocking.

Understanding lock queues in Postgres

When a transaction requests a lock that conflicts with a lock already held by a different transaction, it enters a lock queue. By default, the requesting transaction will wait indefinitely until the lock becomes available. These waiting locks form a queue, but this queue, unfortunately, is not directly visible in the pg_locks system view. Instead you can use the pg_blocking_pids() function to identify which backends are blocking a specific backend.

The locks that are ahead in the queue can block locks that are behind them, leading to cascading delays. For example:

- A long-running

SELECTholds an ACCESS SHARE LOCK. - An

ALTER TABLE DETACH PARTITIONneeds a brief ACCESS EXCLUSIVE LOCK - But they conflict so

ALTER TABLEis placed in the lock queue. - Another 20 backend is trying to do simple primary key lookup

SELECTs. - But they conflict with the

ALTER TABLE's lock so they are queued behind theALTER TABLEoperation. - All access to the given table is now queued behind and no processing happens until the long running

SELECTand theALTER TABLEboth finish.

This cumulative waiting can significantly impact performance, especially in high-concurrency environments. Use lock_timeout to limit how long a transaction waits for a lock. For DDL operations, setting a lock_timeout is often enough to prevent complex waiting scenarios. However, when implementing timeouts, your application must be prepared to handle failures gracefully, typically by implementing retry logic for the DDL operations that timeout.

The biggest insight from this is that any long-running query can cause blocking during schema changes, but this cumulative waiting effect can be mitigated by setting appropriate lock_timeout values.

We also have a good blog post on Schema changes and the Postgres lock queue, in case you'd like to read more.

Locking it all together

I've noticed that this blog has become quite long, and I have much more to say. So, I will end it here and write a follow-up to discuss lock contention and ways to minimize the impact of locks where necessary.

So far, we've explored how MVCC helps handle concurrent transactions and how the various lock modes protect data integrity. We've seen that locks range from more permissive ACCESS SHARE to more restrictive ACCESS EXCLUSIVE, each playing a crucial role in maintaining data consistency. While MVCC avoids many traditional locking issues, some level of locking remains unavoidable. The key is finding the right balance, too little locking risks data corruption, while too much creates unnecessary bottlenecks.

To summarize, here are the key takeaways from this blog:

- MVCC will protect you from writes blocking reads, but not from object locks taken by DDL.

- Different variants of the same DDL command may need very different lock strength.

- DDL may block writes and/or reads for the whole run time of the transaction.

- Don’t mix commands that need strong locks with others working in same transaction.

- Use

lock_timeoutto limit how long something waits for lock. - Using

lock_timeoutfor DDL commands is often enough. Must be able to handle failures, for example retry the DDL again.

I'll be presenting this topic at PGDay CERN on 17th of January, if you're around, please come by and say hi!

Stay tuned for the upcoming blog post.

Related Posts

Anatomy of table-level locks: Reducing locking impact

Not all operations require the same level of locking, and PostgreSQL offers tools and techniques to minimize locking impact.